One of my favorite subjects to discuss with dancers is turnout. As a dancer, I have often heard “turnout from your hips!”, but it wasn’t until I became a physical therapist and dance science researcher that I learned there is SO much more to it. This post is a summary of a recent deep-dive I did on the topic that is also heavily influenced by my decades as a dance artist and informed by clinical experience treating dancers. I’ll cover ideal versus functional turnout, anatomical contributions that determine how much turnout a dancer has available, and thoughts on how to maximize turnout potential. I will also touch base on what constitutes “forcing turnout” and the related risk of injury associated with improperly turning out. My hope is for dancers and dance educators to have a deeper understanding of turnout and how to reach turnout goals safely.

First, lets define turnout

Turnout is the external rotation of the lower extremities. There are two classifications of turnout: ideal turnout and functional turnout. Ideal turnout is defined as a total of 180˚ of external rotation of the lower extremities and is often the aesthetic goal for many classically trained ballet dancers. Functional turnout is what is possible for an individual dancer based on their unique anatomy and their neuromuscular control over the turnout range. A dancer’s functional turnout may be less than the “ideal” turnout of 180˚, and is not static: the functional turnout range can change as a dancer moves through different dance positions and over time as well. As dancers gain experience, their functional turnout may increase. Injuries may cause a decrease in turnout, both during rehabilitation and potentially over the rest of a dance career.

I’m going to focus specifically on functional turnout in dance, with special care given to how anatomical features (that vary from person to person) affect the range of functional turnout that a dancer can use.

Where does turnout come from? (drumroll, please!)

Yes, turnout primarily comes from the hip joint BUT we also have contributions from the tibia, the foot/ankle complex, and if the knee is bent, the knee joint! Many dancers and instructors stress the importance of turning out from the hip joint, which is the correct way to initiate turnout in dance (more on this later)- but it is incorrect to assume dancers get ALL of their turnout range from the hip joint alone.

Turnout contributions from the hip joint:

One study took passive hip external rotation measurements of 1,314 dancers aged 8-16. The researchers found the average hip external rotation range of motion to be between 51 and 60 degrees.7 Even if a dancer is hypermobile and has, say, a whopping 70˚ of hip external rotation, that still only accounts for 140˚ of turnout.

It is important to note that contributions from the hip joint can vary among dancers due to anatomical differences, primarily due to something called femoral torsion.

Femoral torsion describes the structural rotation of the femur (thigh bone). There is femoral anteversion, inward rotation of the femur, and femoral retroversion, outward rotation of the femur. Femoral torsion can change the alignment when comparing the portion of the femur at our hip versus the portion of the femur at our knee. The amount of femoral torsion can vary, as there are many contributing factors to how our bones take shape due to genetics and our environment. Most individuals have varying degrees of femoral anteversion (inward rotation). However, when we are young and growing, our bones are vulnerable to change from repeatedly moving within an externally rotated position. Compared to NARPs (non-athletic regular people) dancers commonly have less femoral anteversion, likely due to many dancers externally rotating their legs to turnout at a young age.1

In the image above, we can see what would be “normal” femoral anteversion from a birds-eye view of the hip and lower extremity- the foot faces forward and the proximal femur sits mid-range within the hip socket. Dancers with less than average femoral anteversion (or if significant, “femoral retroversion”) can be seen walking with what looks like both legs turned out, or “duck walking”. These dancers (below in green) have a greater range of hip external rotation because their femur is positioned towards the back surface of the joint.

Dancers who have greater amounts of femoral anteversion (seen below in orange) will have less hip external rotation due to the proximal femur being positioned towards the front of the joint. Theoretically dancers with a shallow hip socket that faces more towards the side, and a long femoral neck with less femoral anteversion would have greater turnout access from the hip.3 Just know anatomy can vary, which is why a dancer may not have the same amount of hip external rotation available compared to peers or their instructors’ expectations.

Turnout contributions from the tibia:

The second greatest turnout contribution comes from our tibia (aka shin bone). Similar to our femurs, the tibia is also vulnerable to rotational stress applied throughout years of dance training when we are young. The axial rotation of the tibia is known as “tibial torsion”, which can be seen below. Notice how if we were to take a cross-section image of the proximal (upper) tibia and compare it to the cross-section of the distal (lower) tibia, the distal end would be angled outward or externally rotated.

Interestingly, some dancers may have greater turnout contributions from external tibial torsion than from their hip joint! Recently I measured a dancer’s hip external rotation range of motion at around 40 degrees. That’s quite limited compared to what I had been expecting, knowing the high level of training and turnout demands at that dancer’s school. I then measured the dancer’s tibial torsion and saw they had around 45 degrees on both legs. This dancer receives the majority of their turnout not from their hip joint, but rather from the rotational alignment of their tibia: 40+40+45+45 = 170 degrees of turnout from the hip and tibia alone!

Also interestingly, tibial torsion can vary among dancers and even between each of a dancer’s legs! In one study, researchers used MRI to measure the tibial torsion of 14 collegiate BFA dancers. The dancers averaged around 35 degrees of tibial torsion on the right leg and 33 degrees on the left.5 These averages were slightly above the 24-30 degrees of normal external tibial torsion in NARPs.6 The MRI study revealed many different tibial torsion measurements when comparing right and left legs. The most striking difference was a dancer with 45˚ of tibial torsion on the right compared to the 29˚ on the left! The highest degree of tibial torsion measured was 60˚; the minimal amount was 16˚.5 While ideal turnout is 180˚ with 90˚ of contributions from each leg, this information implies a dancer may recruit turnout unequally between two legs from the shape of their bones alone!

Turnout contributions from the knee joint:

Turnout contributions from the knee joint depend on if the knees are straight or bent.

Technically speaking, when initiating turnout at the start of most ballet class combinations, we should start with the knees fully straight and have limited amounts of turnout available at the knee joint due to the screw home mechanism.

However, when the knee is bent between around 30-90˚ (like when sitting in a chair) researchers have measured ~45˚ of external rotation mobility available at the knee. Once the knee straightens just 5˚ shy of fully-extended we can anticipate half the amount of external rotation available.8 Once the knee is fully straight and the screw home mechanism occurs, our knee should be stable and not making significant contributions to turnout.

A common way I see dancers forcing turnout is by finding first position when their knees are slightly bent, using the friction of the floor to rotate outwards from the feet and upwards, and then straightening their knees while maintaining this over-rotated position (I will own up to it… I’ve been guilty of this in the past!) This turnout mechanism places a lot of unnecessary stress on the knee joints. If I have a dancer experiencing knee pain in the clinic, one of the first movements I want to review is how they are initiating their first position turnout and ways to minimize strain on their injured tissues. Educating these injured dancers on how to appropriately find their turnout is a game changer in rehabilitating a dance injury – but it is only effective if the dancer is open-minded and can shed their “ideal 180˚ turnout” mindset while prioritizing their functional turnout range.

Turnout contributions from the foot and ankle:

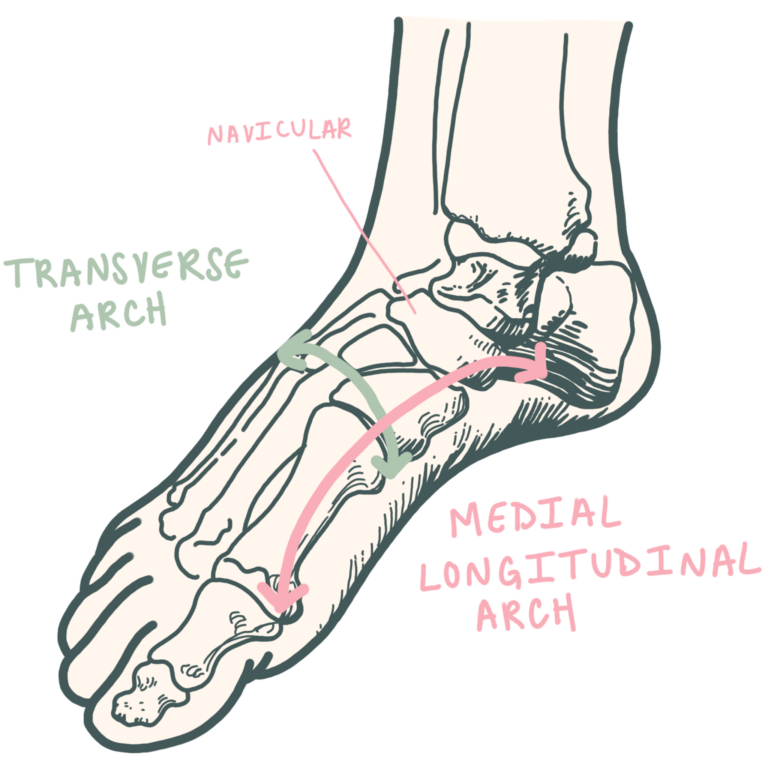

Turnout contributions from the foot and ankle are poorly defined and not studied as much as those from the hip joint. Research shows that dancers with a lower medial longitudinal arch can access more turnout through functional pronation of the foot. However, this can also be a way for dancers to force their turnout: if using the friction from the floor, they will maximize the turnout potential at the foot and ankle before utilizing the hip joint contributions. You may have heard a cue to avoid “rolling in” at the foot. That means to stop over-pronating the foot as a way to force turnout.2

Is it possible to have 180 degrees of turnout?

I have been on team “yes!” and on team “no way!”, but now I’m on team “it depends!” According to a study by Grossman et al, which combined measurements of dancers’ hip external rotation mobility and tibial torsion, a few of the dancers had access to MORE than 90˚ of turnout per leg based on their joint mobility and tibial torsion (!!!). The same study also measured functional turnout using frictionless discs and compared the results to passive turnout measurements of the legs where an examiner moved the dancers’ legs into position to maximize turnout potential at each joint. When comparing the turnout measured with the frictionless discs to the passively measured turnout, the dancers exhibited less turnout on the frictionless discs. In fact, they averaged 22˚ less on the right leg and 19˚ less on the left leg.5 Based on those measurements, if we have a dancer with access to 180˚ of passive turnout they may be able to actively turnout only 139˚ due to muscle weakness. In all, the study revealed that many dancers truly lack the strength of the hip external rotator muscles to achieve full turnout potential.5 Therefore, dancers and dance instructors should spend less time stretching for turnout range and much more time strengthening that range.

If you watch a ballet class you will also see that dancers can access more turnout when at the barre, compared to in the center, from the stability the barre provides the upper body and trunk. Dancers can more easily force their turnout at the barre too, relying on the barre to help ground themselves on overly-rotated legs from the friction of the floor. Then once the dancers get to the center, they are unable to access that same turnout range due to lack of neuromuscular control, muscle endurance, and strength.

In the clinic, I will first observe HOW the dancer finds their first position, then I will measure a dancer’s hip external rotation range of motion using a goniometer, their tibial torsion using an inclinometer, and then add the values together to determine the estimated passive turnout range. Then I will measure the active turnout range of each leg by having a dancer externally rotate on a frictionless disc and measure the range with a goniometer. I have yet to see a dancer access 100% of their turnout potential — many lack the hip external rotator strength.

How can we improve turnout?

Many dancers lack the strength of their hip external rotator muscles to reach their full turnout potential.5 Therefore, turnout can improve by conditioning the rotators to be stronger and have more muscle endurance capacity, and by training to increase neuromuscular control. Our primary hip external rotator muscles are:

- Piriformis

- Obturator internus

- Obturator externus

- Gemellus superior

- Gemellus inferior

- Quadratus femoris

Depending on the specific dance position, the gluteus maximus, sartorius, and biceps femoris may contribute to hip external rotation and turnout.3 I would go further in detail on specific exercises that may improve a dancers turnout, but the truth is that each person is unique and there is not a “one size fits all” program. In the clinic I provide dance artists with carefully-targeted, specific exercises to improve their strength, muscle endurance, internal rotator muscle flexibility, and joint mobility.

Studio Diamonds

In the medical world, we refer to the key takeaways of a topic as “Clinical Pearls”. Here at Baseline Dance, we call these “Studio Diamonds”:

- “Ideal turnout” is 180˚, while “functional turnout” is the true turnout potential a dancer has based on their unique anatomical contributions and muscle control

- Turnout potential = hip external rotation range of motion + tibial torsion + foot and ankle contributions

- If the knees are bent, we can also have turnout contributions from the knee joint

- Increased femoral anteversion is the main reason a dancer may lack turnout range at the hip joint

- Turnout should be initiated by activating the hip external rotators, located in the gluteal area (posterior hip)- and not at the front of the hip as some dancers believe

- Using the friction of the floor to wind-up the joints from the ground up is considered forcing turnout. While it has the potential to be aesthetically pleasing it should not be praised or encouraged by educators and peers, as this places dancers at risk for severe injury and loss of career performance time. 🙁

- Dancers should prioritize conditioning hip rotator muscles, as dancers commonly lack the strength, control, or muscular endurance to maximize the turnout range anatomically available to them – dance class alone just does not cut it.

- Dance instructors should not expect all dance students to have 180˚ of turnout. Every body is different.

If you experience pain when you dance please consult a licensed physical therapist or your healthcare provider. Bonus points if they are familiar with dance!

Did you enjoy the post? Check out more Dancer’s Guides and our shop!

References

1.) Angioi et al. An Updated Systematic Review of Turnout Position Assessment Protocols Used in Dance Medicine and Science Research. Journal of Dance Medicine and Science. 2021.

https://doi.org/10.12678/1089-313X.031521h

2.) Carter et al. An analysis of the foot in turnout using dance specific 3D multi-segment foot model. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13047-019-0318-1

3.) Clippinger, Karen S. Dance anatomy and kinesiology. Human Kinetics. 2007. ISBN-10: 0-88011-531-9

4.) Goldsmith et al. Correlation of femoral version measurements between computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging studies in patients with a femoroacetabular impingement-related compliant. Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery. 2022. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnac036

5.) Grossman et al. Reliability and Validity of Goniometric Turnout Measurement Compared with MRI and Retro-Reflective Markers. Journal of Dance Medicine and Science. 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229071020_Measuring_dancer’s_active_and_passive_turnout

6.) M. Snow. Tibial Torsion and Patellofemoral Pain and Instability in the Adult Population: Current Concept Review. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09688-y

7.) N. Steinberg, I. Siev-Ner. Screening the Young Dancer: Summarizing Thirty Years of Screening. Prevention of Injuries in the Young Dancer. Springer Publishing 2017. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-55047-3

8.) Zarins et al. Rotational motion of the knee. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1983. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658301100308